Do you know how and why getting to a healthier weight will relieve some of the symptoms of anorexia?

Getting to a healthy, or at least healthier, weight is the hardest thing in the world when you have anorexia.

Some people I have worked with have told me that nobody has really told them why, other than ‘just because’ or it will make them healthier, whatever that means.

You might know you are an unhealthy low weight, even if you don’t feel it. You may have a sense, or have been told, that you will be better, or feel better, or at least be free of the worst of the difficult thoughts, if you could just get over the brow of the hill to a healthier weight.

I think it must make the hill harder to climb if you don’t understand quite how or why it might help you.

In this post I am going to explain how getting to that healthier weight might help with two very specific symptoms of anorexia: low mood and hyperactivity/restlessness.

I am going to share information on a key appetite hormone called leptin that plays a big part in anorexia and anorexic ‘cognitions’ and behaviours. This information is likely to be different from anything you have read before about why you feel the way you do.

I hope that by providing some of the science behind these thoughts, feelings and sensations, it might help you to understand how leptin, or its absence, might contribute to the symptoms you are experiencing. It might also help you view weight restoration in a different light, as a tool to correct a leptin deficit.

The famine hormone

Leptin plays a crucial role in our adaptation to dietary restriction. For this reason, it has been dubbed the ‘famine hormone’. It is made primarily by our fat cells and acts as a sensor of nutritional stores. It reports back to the hypothalamus and other structures in the brain that are involved in appetite and homeostatic regulation. In this way it plays a part in controlling the functions of our body, and the responses of our brain, to nutrition availability and stores.

Amongst other things, leptin controls fertility in famine and fertility resumes when the body is confident that nutritional stores are adequate. This ‘adequacy’ is sensed by leptin levels – low levels and fertility is switched off, adequate levels and it can be switched back on again. It is a clever strategy from an evolutionary point of view, to prevent babies being born when there is food shortage. Not that much is random in our bodies.

Leptin levels are very low in people with anorexia. Below is a graph from an older review paper (I haven’t found another review with a nice visual) which shows you an example of leptin measurements in women with anorexia, compared to healthy controls. You can find a list of the studies of leptin levels in anorexia in this paper.

You cannot, by the way, get this measured in the NHS, not at the moment at least.

Leptin also exerts profound effects on how we feel and think. This is not really surprising, as part of its role is to restore nutrition and make us perform those behaviours necessary to do this. It is important to remember that these functions evolved hundreds of years ago, when we were hunter-gatherers and have, in many ways, kept humans as a species alive and well. I am a bit of a biology fan-girl and am in awe at how evolution has thought of every eventuality.

Depression

One way that leptin influences our behaviour in a famine is by making us depressed. Even rodents seem to get depressed when starved. We don’t entirely know why, but I like to think it is to make us want to move away from where we are, an environment where food was scarce, to find a better place with more abundant food supplies. The effect of leptin on mood is so profound that leptin resistance in the brain, where leptin levels are normal, but the message is not passing to the hypothalamus, is being studied as one of the reasons why people living with overweight and Type 2 diabetes seem to be more depressed than people with neither.

For those of you familiar with the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, depressed mood was one of the most significant symptoms the men experienced during the starvation phase.

There are a couple of rare conditions where people don’t make enough leptin – congenital leptin deficiency and a condition called lipodystrophy. People with lipodystrophy suffer with low mood – as many as 56% have a diagnosable mood disorder.

Recombinant human leptin, a synthetic analogue of the human hormone leptin, exists as a medication. It is called metreleptin.

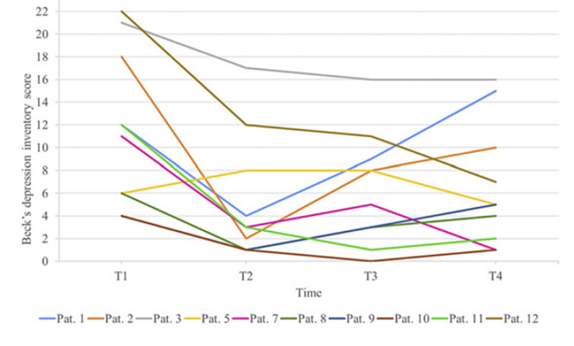

Below is a chart showing mood in 12 people with lipodystrophy before and after they were treated with injected metreleptin. Each line and colour represent one patient. T1 is their baseline depression scores using a validated tool (Beck’s Depression Inventory), T2 1 week after treatment starts, T3 4 weeks into their treatment and T4 after 12 weeks of treatment. Can you see the change in mood that leptin alone brings?

I imagine a few of you reading this will be focussed on Patient 1, the blue line. We don’t know too much about the life circumstances of the patients measured and studied, as the paper doesn’t report this detail. Who knows what happened to him or her? Try and see the overall trend in all patients combined instead. Nine of the 10 patients had a lower BDI score at T2 in comparison to baseline (T1).

Metreleptin in anorexia

There is a researcher in Germany who you may have heard about called Professor Johannes Hebebrand. He has been researching leptin in anorexia from almost when leptin was first discovered. (It was discovered in 1994; he started anorexia and leptin research in 1995.)

In the beginning, he measured leptin in people with anorexia and in rodents who were subjected to an animal model designed to mimic anorexia.

More recently, he has been administering leptin to people with anorexia ‘off-label’ (it is not licensed for this use. Yet.). His colleague Gabriella Milos is now conducting the first randomised controlled trial of metreleptin in anorexia. This may well be the first treatment to emerge for anorexia.

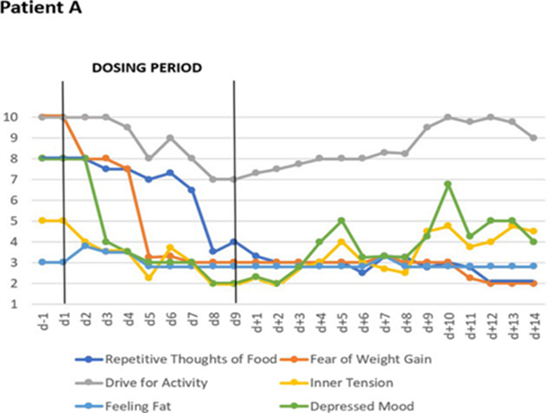

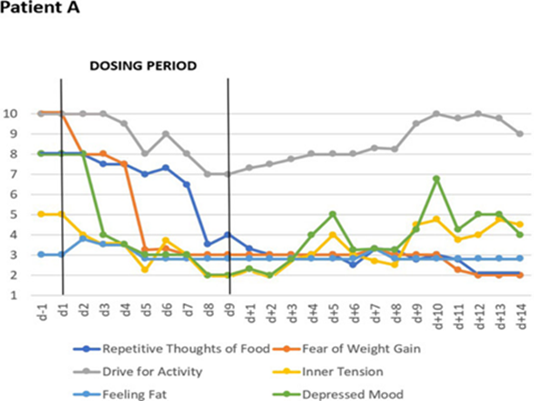

Below you can see the effect of metreleptin on mood in one person with anorexia. The green line represents ‘depressed mood’. d-1 is the day before metreleptin is administered. d1 is the first day of metreleptin treatment, which carries on until d9, or Day 9. By Day 3 the symptom of ‘depressed mood’ had dropped dramatically.

Hyperactivity

The second feature of leptin that I want to talk about is its role in Starvation-Induced Hyperactivity (SIH). This behaviour is very well described in famine situations. Fritz Schilling, at the time a German soldier, was taken into Soviet captivity during World War 2. After being released in 1947 he wrote about his experience of being held captive on hunger rations. He describes a ‘restlessness’ and ‘tremendous work’ [i.e. the urge to work].

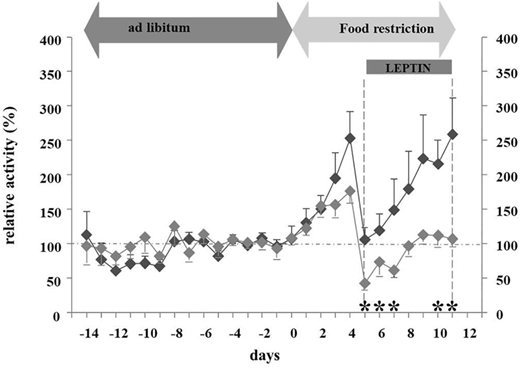

In the chart below, you can see the effect on Starvation-Induced Hyperactivity (SIH) of leptin infusions in a rodent model of anorexia. In the first part of the chart, the rodents were given free access to chow. In the second half, their food rations were cut to 60% of their pre-restriction intake. The top line and dots represent the rodents that were not given leptin, the bottom line and dots the animals that were given leptin via infusion. Can you see how those animals that were not given leptin developed hyperactivity, while those that were did not, compared to baseline?

In a famine, leptin plays a role in increasing foraging behaviours, to help us find food. One of these behaviours is hyperactivity, or the need to walk or run and to look for food. Dopamine is upregulated to facilitate this, which makes research animals move more. Food restriction reliably leads to hyperactivity in rodent models of anorexia and starvation.

In people with anorexia, this is often felt as a drive or an urge for activity, jittering and restlessness.

Below, and using the same image as we used for ‘depressed mood’ earlier in this post, you can see the effect that administering metreleptin has on the sensation of restlessness in one case of a person with anorexia. The grey line represents that ‘drive for activity’ and the yellow line ‘inner tension’. d-1 is the day before metreleptin is administered. d1 is the first day of metreleptin treatment, which carries on until d9, or Day 9.

The table below shows an excerpt of a summary of the case studies Hebebrand has published. Under the ‘Impact’ column, a + sign indicates an average 30% improvement or more in that symptom, a ++ an average 50% improvement or more. Under the ‘Frequency’ column, a +++ indicates that more than 50% of patients experienced an improvement in this symptom.

| Symptom | Impact | Frequency | n |

| Inner tension | + | +++ | 10 |

| Urge to move | + | +++ | 10 |

| Depressed mood | ++ | +++ | 10 |

Do people with anorexia become ‘entrapped’ in a state of low leptin levels?

Hebebrand believes that, after the initial weight loss, people with anorexia become ‘entrapped’ in a state of very low leptin levels. He believes that this state perpetuates the feelings, thoughts and behaviours of anorexia, making it difficult for people to break free from this state of ‘hypoleptinaemic entrapment’.

Can you see how raising leptin might help with two particular problems you might be experiencing: a drive for activity, a restlessness, and also low mood or outright depression? Of course, there are other reasons for depression in anorexia, and I will come back to these in another blog post, but low leptin levels will most certainly also play a very significant part.

Can I not just take leptin?

You might be asking: ‘Can I not just take leptin?’ This might seem like the easiest answer, and one day this may be a treatment for anorexia, but right now it is not licensed for this use. Unfortunately, the answer is therefore ‘no’. All we have now is the hard work of restoring leptin to your baseline level, or a healthier level, through weight restoration. This will send a message to the appetite regulatory structures and their downstream connections in your brain that the famine is averted. Time to switch off the famine survival responses in your body and brain, to end the entrapment.

Hopefully, you might be able to see weight restoration in a little bit of a different light, as leptin restoration or correction. Can you start to think about how each day, with each meal or snack, through each mouthful, you are increasing your leptin levels? Can you even say this to yourself: ‘I’m increasing my leptin’ rather than ‘I’m putting weight on’? Does it help to understand biochemically how a nebulous and scary notion of weight gain will, slowly, bite by bite, reduce the tension you feel like a taut rubber band, the restlessness, the fidgeting. It may also lift some of the flat feeling of ‘anhedonia’, depression, that you might be feeling?

Has this knowledge helped you in any way? Do you have tips for other readers on how to apply this to your recovery journey?

Thank you to Bella @anorexiamyths.com for reviewing a draft of this post.