Winter is coming – what does this mean for appetite?

Why do we get hungrier as winter approaches and what does this mean for those with anorexia?

The arrival of autumn marks the beginning of a difficult season for those with an eating or appetite disorder.

For those with anorexia, autumn can be a particularly challenging time, when difficult thoughts and feelings intensify.

It also marks the start of the busy season for those who work in adolescent eating disorders, as a month or so after the schools and colleges go back is typically the first peak for new presentations of anorexia in teens.

For those with bulimia, binge eating disorder (how I hate that phrase!) and people living with obesity, autumn is the start of the hungry season, when your appetite seems almost insatiable. You can’t seem to get full in the same way and you are just so hungry again, so quickly.

It is these same changes that cause animals (as well as humans!) to hoard. So, the squirrel frantically burying his nuts in your lawn is driven by the same processes that are making you repeat your journey to the kitchen for a snack for the umpteenth time today, or that are driving the incessant food thoughts that have dominated your day.

In this post I am going to talk about some of the biological changes that happen to our brains and bodies as autumn arrives to prepare us for the, once upon a time, hard and lean winter ahead. I am also going to explain what happens to people with anorexia that is a bit different and what this might mean if this is you. Hopefully this post will help you to understand why you might be experiencing some of the feelings and sensations that you are.

For those of you struggling with eating more than you think you should, understanding how our mind and body work helps us to accept what is happening for us and to see both our body and our mind with more kindness. They’re often only trying to do their jobs.

For those of you, or a loved one, struggling with anorexia, I am going to share a tip for how we might harness this quirk of evolution to help relieve mealtime anxiety.

What happens to make us so hungry?

A significant source of these phenomena are the appetite hormone/peptide and neuronal changes that happen with the changing season. Most of these are the result of careful evolutionary selection that have enabled humans (and other species) to survive the harsh winters that once were, so that you and I are here today.

You might have heard that we get hungrier in the autumn because our nutritional needs are higher in the winter. They’re actually not, not for people in a healthy weight body at least.[1] But once upon time, they were. Back when before central heating, indoor jobs, cars and heated trains and buses, our needs were higher in the cold. In a time before modern food production, distribution and storage, winter could also be time of hardship and food shortages, where nothing grows and winters were lean. Our clever bodies have evolved a few mechanisms that make us resilient to these threats.

Let’s find out more and delve into the changes that occur as soon as the temperature drops, and the light diminishes.

Leptin drops

First of all, a drop in outdoor temperature causes a drop in leptin (and here), a satiety hormone, and a rise in hunger-generating hormones. The temperature difference is sensed by keratinous cells in your skin. Humans have an abundance of keratinous skin cells in the palms of our hands and on the soles of our feet. Keep your hands and feet warm is the message here!

For the super nerds amongst you (me!) TRPV4 channels (TRPV stands for transient receptor potential vanilloid) in the skin are activated at temperatures of 25-34°C. These channels also exist in fat cells, and their activation increases leptin production. See below regarding the application of heat in anorexia.

The seasonal drop in leptin, for those without an eating disorder, causes an increase in appetite. This is because leptin, as it passes through to the arcuate nucleus in our hypothalamus, tells the POMC neurons there to make a protein (a-melanocyte stimulating hormone, a-MSH for short) that signals satiety. Lose leptin and you lose the satiety signal – your brain thinks you’re heading into a famine. Which once upon a long time ago you may well have been.

POMC neurons are down-regulated

It’s not just that leptin drops, reducing the message to the POMC neurons, but, in rodents at least (we can assume the same happens in humans) the neurons themselves are down-regulated with the changing light, meaning production of their crucial satiety-signalling peptide (protein) hormone a-MSH is put on pause. Another hit to appetite regulation.

Agouti-related peptide is upregulated

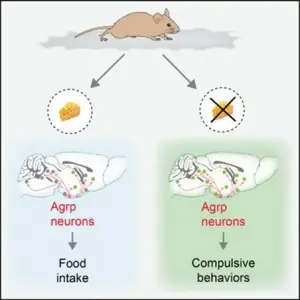

The change in light also increases the expression of an appetite stimulating hormone (also a peptide actually) called agouti-related protein (AgRP). AgRP is a powerful stimulator of appetite and, if not allowed to do what it is meant to do, that is make us eat, the devil will find work for its idle hands and it turns its attention, again in rodents, to ‘displacement activities’.

When the neurons that produce AgRP are stimulated in lab rodents, but they are not allowed to eat, foraging and displacement activities emerge instead. Activities such as excessive grooming, aimlessly digging and pointlessly burying stones, and obsessive running in their wheels.

These behaviours mimic many OCD behaviours in humans and specifically, the types of behaviours that the men in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment experienced – fantasising about food, collecting cookbooks, sorting food on their plates, hoarding.

We already know that AgRP is raised in anorexia as you would expect – it goes up when the body is malnourished. We might assume therefore that upregulation of AgRP as winter approaches would increase ruminating thoughts and rituals in an already malnourished body.

Melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) neurons are activated by cold

Melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) is another powerful orexigenic (meaning it increases appetite) peptide. MCH encourages us to eat more fatty and sugary foods, so a rise in this as winter draws near is a clever evolutionary quirk designed to increase energy stores. MCH also encourages us to carry on eating once we have started and plays a crucial role in a process called ‘Flavour Nutrient Learning’, i.e. learning to like foods that are good sources of energy.

MCH is increased by almost 60% in cold-exposed animals providing yet another mechanism to increase our intake. It is involved in food memory and reward, particularly regarding higher calorie foods, so may be involved in a pull towards ‘comfort’ foods with the autumnal change.

Is this different for people with an eating disorder?

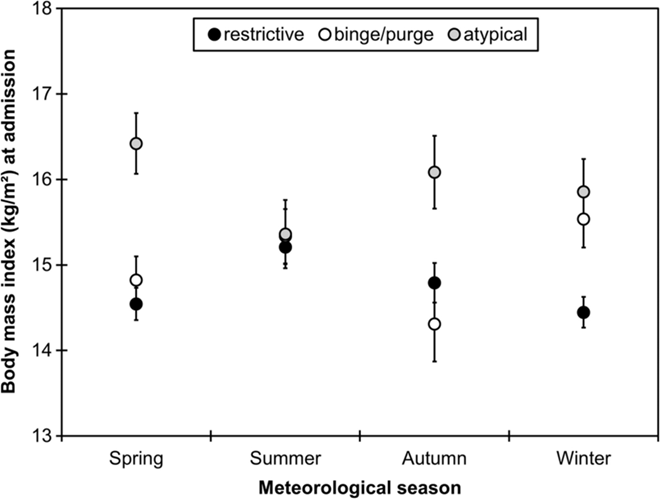

Overall, patients with restrictive anorexia have lower body weight if admitted in the autumn and winter months than in the summer and spring. For example, the image below is taken from a study of 606 inpatients (95.4% female) admitted for treatment for anorexia between 2014 and 2019. Patients with restrictive type anorexia (AN) had lower body mass index at admission in the winter than in the summer. This difference was not found for patients with binge/purge type anorexia nor for patients with atypical anorexia.

This trend has been found in other studies too (here and here).

This is the opposite trend from the rest of the population, who tend to be heavier in the winter months. Why is this?

As far as I’m aware, there isn’t a definitive answer, but I’m going to make a few guesses. Firstly, it might be that autumn and winter lead to an increase in anorexia symptoms and lower body weight, for whatever reason (greater energy expenditure when it’s colder without insulting fat stores, induced by the change in light?), leading to more entrenched hypoleptinaemic entrapment and with that, greater risk of hospitalisation.

Secondly, it might be that the seasonal drop in leptin worsens the hypoleptinameic entrapment of anorexia, leading to lower weight, lower leptin and so on, in a downward spiral. Lower leptin will increase depression, hyperactivity, probably also anxiety. These factors, along with greater physical risk from lower body weight, possibly increases the risk of hospitalisation.

A third and alternative view is that the seasonal drop in leptin exerts some other biological effect to increase anorexia symptoms. For example, leptin plays a very important role in the functioning of our immune system, and mediates seasonal changes in our immune response.

A fourth possible explanation, and the most controversial of all, is that the winter surge in respiratory infections plays a role.

My hunch is that the seasonal drop in leptin, along with the rise in seasonal infections, play a role in the increased incidence of new onset anorexia in teens that we observe in eating disorders services soon after the schools and colleges go back. I will elaborate on this in a future post, so sign up to hear when it’s published.

It is also worth noting that low leptin, or leptin deficiency, reduces body temperature and induces the cold sensitivity of undernourishment. We know that people with anorexia have very low leptin levels.

Can heat help anorexia?

A few clinicians and researchers in the eating disorders field have recommended warming people with anorexia. For example, Per Södersten writes that at some clinics in Sweden, this is common practice. Remarkably, William Gull, one of the first doctors to study and write about anorexia, wrote in 1873:

‘I have observed that in the extreme emaciation when the pulse and respiration are slow, the temperature is below the normal standard. This fact, together with the observation made by Chossat on the effect of starvation on animals and their inability to digest food in the state of inanition without the aid of external heat, has direct clinical bearings—it being often necessary to supply external heat as well as food to patients. The best means of applying heat is to place an India rubber tube, with a diameter of 2 inches and a length of 3 or 4 feet, filled with hot water along the patient’s spine, as Dr. Newington of Ticehurst suggested (p. 24).’

Tubes of India rubber aside, modern research has shown that access to a heat pad reduces the hyperactivity associated with semi-starvation in animal models of anorexia. Heat also enables the animals to eat more than those without a heat pad.

I find this especially fascinating, because of the findings of a physiologist and physician called Charles Chossat in the early days of starvation research. His animal experiments would be considered both cruel and unethical by today’s standards, but in 1843 he starved a total of 48 animals, including pigeons, fowls, guinea pigs, tortoises, snakes and frogs, so that he could study the effects of starvation on various species. He discovered that, at a body weight loss of 20%, his animals were unable to recover from starvation when provided with food and had to be hand fed, unless they were placed in a warm stove.[i]

Access to a heat pad also reduces AgRP expression and expression of the key receptor that signals satiety in our brains, the MC4 receptor. I’ll come back to why this latter is significant in anorexia in another blog post.

Human research shows that the application of heat reduces anxiety symptoms in anorexia, particularly around mealtimes. This might be because raising the temperature increases leptin (also here). Another study showed that wearing heat vests for three hours per day also helped alleviate some of the gastrointestinal discomfort that is common. In any event, it is unlikely to be harmful. The first study used a temperature of 32oC, the second 30oC, and the third doesn’t tell us the exact temperature.

If you want to read more about heat in the activity based anorexia (ABA) rodent model, including the history of several accidental and serendipitous findings (mainly involving faulty electrics!), I recommend this study by heat-in-anorexia researcher Emilio Gutierrez at the University of Santiago in Spain. Do be warned that if you object to animal research, this paper might be difficult for you to read.

Enough from me and over to you. Have you found that you are struggling more with difficult thoughts as the season has changed? Have you found ways to help with this? What has worked for you that you could share with other readers? Are you a parent perhaps, and this resonates with your experience? What has worked for your child?

I’m particularly interested to hear if you have experience of using warmth – has this reduced anxiety? Increased it? Something else? Please share your thoughts below or let me know via email if you prefer.

Thank you to Bella @anorexiamyths and J. a mental health nurse who treats adolescents with an eating disorder for their review of a first draft of this post.

[i] Chossat C. Recherches expérimentales sur l’inanition. Sciences Mathématiques et Psysiques. 1843;8:438-640; Chossat, C. Recherches Experimentales sur l’Inanition, Edinb Med Surg J. 1844 Jan 1; 61(158): 155–162.

[1] Bodies without the usual subcutaneous fat insulation do however lose more heat.